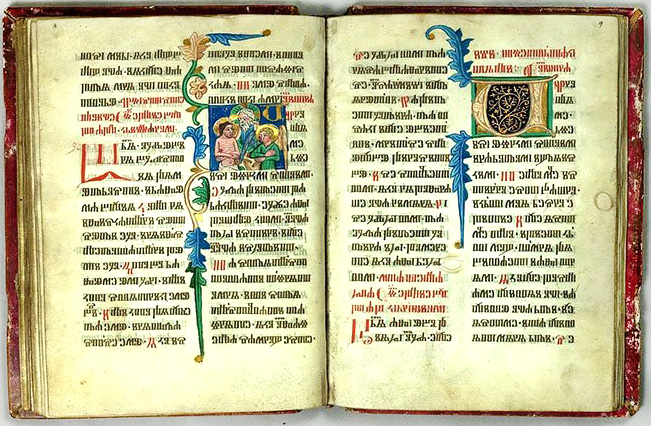

Photo. Reims Gospel, artefact in the Ukrainian language. Written in both the Cyrillic script and the Glagolitic script, the 40s of the 11th century // https://pustunchik.ua/ua/online-school/linguistics/istoriia-pysmennosti-i-gramotnosti

Denying the existence of the Ukrainian language as the self-sufficient one is a common stereotype, imposed by Russian. Since it is the language which is the significant factor of the nation’s consolidation and self-identification, the depriving of the national language idea makes its nation sensitive to any external influence. Any attempts to frame the Ukrainian language into the dialect of the different language mean the intentions to provoke the doubts concerning the fact of the Ukrainian ethnos existence as a self-identical one. The first of such trials was done by M. Lomonosov who wrote in his linguistic researches that Ukrainian was truly Russian but spoiled by Polish. In the 1840s, V. Belinsky, the Russian publicist, noted: “There is not any Ukrainian language but the collection of regional dialects of Minor Russia (Malorussia)”. During the Soviet period, this idea was transformed. The existence of the Ukrainian language was not denied anymore, but the authorities insisted on that its development began after incorporating the Ukrainian lands into the Magnus Ducatus Lithvaniae and the Crown of the Polish Kingdom in the 14th-15th centuries. Before this, as the Russians claimed, there had been the single Old Russian Language which belonged to the single Old Russian nation.

The linguists confirm that the Ukrainian language meets the criteria of the language by its phonetic, morphological and syntactical arrangement. According to George Shevelov (Jurii Shevelov), the Ukrainian language originates from the Proto-Slavic language, has pass through 6 stages in its development, and the earlier ones coincide with the period of the 7th-11th century.

The Proto-Slavic language existed before the 6th century. Then, the Slavic tribes spread and settled down throughout the European continent actively and developed the unique languages of their nations at the new territories, for instance, Bulgarian, Czech, Polish, Ukrainian, Belarusian and others.

The Old Ukrainian language shaped at the territory of tribes, evidenced in the chronicles (Litopysy), namely, they were the Poliany (the Polianians), the Siverianians (the Severians), the Derevlianians, the Ulychi (the Uliches or Ugliches). They settled at the territories from Volhynia (Volyn) to Chernihivshchyna. As no written evidences concerning their language were left, the comparative linguistics methods were applied and the data were taken from the foreign sources.

Since the 11th century, the numbers of the written sources had been appearing in the Old Church Slavonic language (also called Old Church Slavic) in Cyrillic script. This language was applied by the upper social class, small in number. The population beyond this class was obviously speaking the local dialects of their clans but the written evidences on them have not been available.

The consolidation of the Proto-Ukrainian tribes stipulated the unification of the local dialects and elaboration of the characteristics to grow into the general Old Ukrainian language. Moreover, the Ukrainian language preserves those oldest features of Proto-Slavic, the ancestral parent language, which have disappeared from the other related languages of the Slavic group. This witnesses that Ukrainian originated directly from Proto-Slavic but not from so-called Old Russian. The linguists have pointed out the following original features:

- the ending -у [u] for nouns in casus genetivus singularis: меду [medu], солоду [solodu];

- the endings of -ові [ovi], -еві/ -єві) [evi]/ [jevi] for nouns in casus dativus singularis;

- change from г [h], к [k], х [kh] to з [z], ц [ts], с [s] in nouns in casus dativus singularis and casus locativus singularis: слуга [sluha] – слузі [sluzi], рука [ruka] – руці [rutsi];

- casus vocativus;

- the endings of -ої [oji] for adjectives in casus genetivus singularis: великої [velykoji], доброї [dobroji];

- dativus casus singularis for the pronouns: мені [meni], тобі [tobi], собі [sobi];

- verb form of the first conjugatio for the third person in the Present Tense and the Future Tense: може [mozhe], убиває [ubyvaje];

- ending -мо [mo] in the verbs for the first person pluralis in the Present Tense and the Future Tense: даємо [dajemo], поставимо [postavymo].

Further, one can find many inclusions of the folk spoken language within the written texts of the chronicles: Володимир [volodymyr] (‘Volodymyr’) but not Владимир [vladimir] (‘Vladimir’), літо [lito] but not лето [ljeto] (the both words mean ‘year, summer’), the form of casus vocativus and specifically Ukrainian words as гай [hai] (‘wood’), полонина [polonyna] (‘the valley in the Carpathian Mountains’), etc.

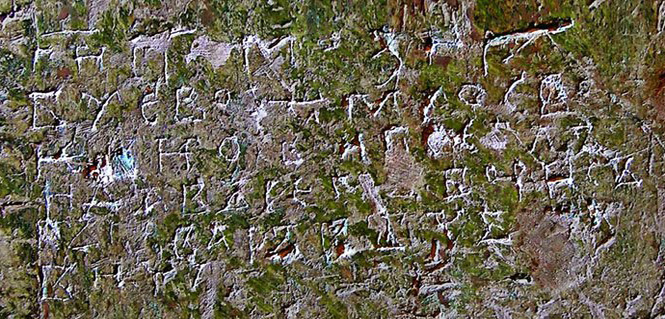

Furthermore, the latest studies on the 11th-12th-century inscriptions cut on the walls of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv have proven that the spoken language of those who produced these inscriptions was Old Ukrainian.

From the above presented, one can deduce that denying the fact of the Ukrainian language existence has no scientific grounds and is purely supported by ideology.

Our advice to read:

Кіндратенко А.М. Походження українців та деяких інших індоєвропейських народів і мов.– Харків: Майдан, 2019.– 245 с.

Лакизюк В. Коли богами були ріки: предки українців та їхні мови.– Київ: Саміт-книга, 2021.– 648 с.

Огієнко І.І. Історія української літературної мови / авт. передм. М. Тимошик.– Київ: Центр учбової літератури, 2019.– 325 с.

Півторак Г.П. Сини Дажбожі, Сварога внуки…: Походження українців, росіян, білорусів та їхніх мов. Міфи і правда про трьох братів слов’янських зі «спільної колиски».– Київ: Видавничий центр «Академія», 2001.

Різників О.С. Спадщина тисячоліть: українська мова. Чим вона багатша за інші?.– 2-ге вид.,

доп., перероб.– Тернопіль: Навчальна книга; Богдан, 2011.– 191 с.– Бібліогр.: с. 185–189.

Федоренко Д., Гузенко Ю. Листи з античної України: сенсаційні свідчення, наукові гіпотези,

історичні доведення про першоукраїнську писемність: посібник.– Київ: [б. и.], 1997.– 176 с.– (Бібліотека українця).