Yaroslav D. Isaievych (1936–2010) is an outstanding Ukrainian historian, academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Ya. D. Isaievych was a director of the Krypiakevych Institute of Ukrainian Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Lviv, Ukraine. Isaievych is known by his books «Fraternities and their Role in the Development of the Ukrainian Culture in the 16th-18th Centuries» (1966), «The Sources on Ukrainian Culture of the Feudal Age in the 16th-18th Centuries» (1972), «Ivan Fedorov, the Father of Book Printing in Ukraine» (1975), «Ukraine, the Ancient and Contemporary. People, religion, Culture» (1996), «Ukrainian Book Printing: Origin, Development and Problems» (2002) etc. Yaroslav D. Isaievych together with art historian Yakym Zapasko prepared the summary catalogue of Ukrainian old-prints “The Monuments of Books Art” (two volumes in three books; 1981–1984). Was editor-in-chief and the co-author of the second volume of “The History of Ukrainian Culture” (2001).

One of the branches of academician Isaievych’s scientific interests was the Ukrainian language, in particular, the Ukrainian language tradition from the early times up to present day. Isaievych substantiated the ideas of the cultural relevance of Ukraine as the direct inherent of the Kievan Rus, though pointed to the artificial character and the academic design of the latter notion, which has not been mentioned in any ancient sources. At the practical array, Isaievych was actively combating the common practice of equating Ancient Rus and Russia in the English-speaking historiography and took efforts for editing the mistake of applying Kievan or Ancient Russia instead of Rus, or Russians when narrate about the ancient Rusyns. Isaievych considered that the English terminology for determining the Ukrainian notions should be of the Ukrainian origin, namely, Kyiv instead of Kiev, as the latter was widely used in the 20th century in foreign publications. Isaievych was encouraging his students and his colleges to be consistent in applying the Ukrainian spelling and pronunciation for the words of the Old Church Slavonic language: “in the quotations in the Old Church Slavonic language, ѣ should not be substituted by Russian е, but is to be preserved or transliterated as і”. The scientist was concerned with the fact that many Ukrainians had lost the intuitive perception of their Ukrainian language, even the native speakers did not detect the artificial character and the Russian-influence in the introduction of such words as «суттєвий», «положення», «книгодрукування», «віддруковано» etc.

One of the branches of academician Isaievych’s scientific interests was the Ukrainian language, in particular, the Ukrainian language tradition from the early times up to present day. Isaievych substantiated the ideas of the cultural relevance of Ukraine as the direct inherent of the Kievan Rus, though pointed to the artificial character and the academic design of the latter notion, which has not been mentioned in any ancient sources. At the practical array, Isaievych was actively combating the common practice of equating Ancient Rus and Russia in the English-speaking historiography and took efforts for editing the mistake of applying Kievan or Ancient Russia instead of Rus, or Russians when narrate about the ancient Rusyns. Isaievych considered that the English terminology for determining the Ukrainian notions should be of the Ukrainian origin, namely, Kyiv instead of Kiev, as the latter was widely used in the 20th century in foreign publications. Isaievych was encouraging his students and his colleges to be consistent in applying the Ukrainian spelling and pronunciation for the words of the Old Church Slavonic language: “in the quotations in the Old Church Slavonic language, ѣ should not be substituted by Russian е, but is to be preserved or transliterated as і”. The scientist was concerned with the fact that many Ukrainians had lost the intuitive perception of their Ukrainian language, even the native speakers did not detect the artificial character and the Russian-influence in the introduction of such words as «суттєвий», «положення», «книгодрукування», «віддруковано» etc.

The problems of the linguistic and cultural relevance were discussed in Isaievych’s scientific publications. The prominent phenomenon of the time became Isaievych’s scientific essay “The Linguistic Code of the Culture”, first published in 1997 within journal “Dnipropertovst Collection of Scientific Works on History and Archaeology” of the History Faculty, Dnipropetrovsk National University, Ukraine.

Below, we propose the summary on this essay.

In order to understand the national culture, one needs to study its linguistic code. What is the role of the language as the form of self-expressing for the culture and the means of its shaping? The language is one of the principal elements of the relevance in the cultural background. The language outlines the ethnic originality for the representatives of a certain culture. The language reflects the processes of the culture shaping, its social diversity and its international connections. The linguistic material is the source for the studies on the culture development, which is relevant to the nation formation and its language.

“The culture is developing as the system of signs, a plurality of symbols and meanings, that helps people to navigate the world and transfer the experience from one generation to the next coming one. But the language itself is the system of signs and it also performs the function of information coding with the purpose of its accumulation, spreading and transferring to the next generations.” The development of culture is a wider notion since it incorporates the language development as its component. The system of language is the general notion. Understanding the processes occurring in a certain culture and its history is impossible beyond the language and the thinking of its representatives, which is tightly linked with the language.

The national languages are formed mainly on the base of the folk-spoken ones, that is why the written form of the language is a version of the same linguistic system. In the Middle Ages, the oral speech was a tool for communication for the whole nation, while the written language was the favour of the privileged class. The knowledge of how to write was restricted and did not come out of the circle of those who were engaged into power. The oldest written language was a sacred one, intended for God worshipping, that explains the respect to those who knew how to read and write.

The Kievan Rus experienced the development of the Old Church Slavonic language, which became the language for the translation of the Gospels and theological books by Cyril and Methodius and their followers. On its base, the language was established to write the chronicles (litopysy), the Lives of Saints, and publicist writing. The scientists are still discussing the term for the language of the ancient writings of the Kievan Rus: it is named as the Ancient Russian Language and as a version of the Old Church Slavonic language. The people who lived in the Kievan Rus did not consider that the languages of the fiction books, litopysy, juridical writings and the spoken version were the different languages, for them, it was the entire language but functionally divided into the three styles to serve the different spheres of life: a sacred one, a governmental one and every-day life. The writings of the Kievan Rus could be read by the Bulgarians, the Macedonians, the Serbs along with the own literature. By that time, the Old Church Slavonic language had acquired the local features of the Slavonic folks, but there were no significant differences between these versions for a long time.

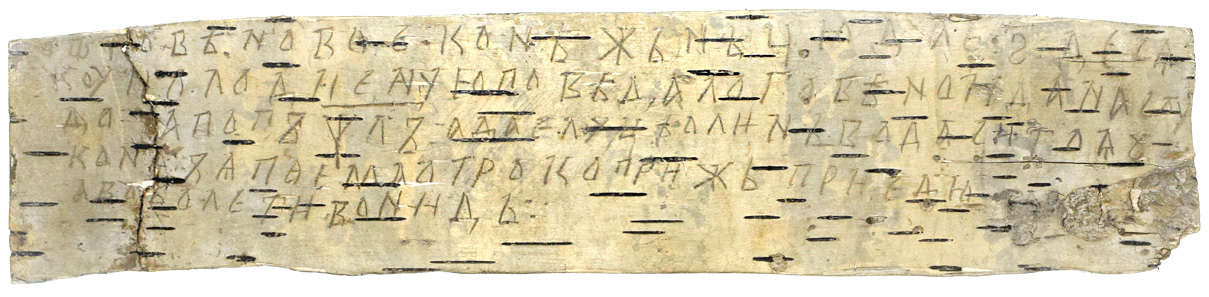

In the 13th and the 14th centuries, the folk-spoken language was represented by the group of closely related Ukrainian dialects, which had developed on the ground of the previous dialects of the Proto-Ukrainian tribes. Unfortunately, the Ukrainian ethnographic array was not so well evidenced as that of Old Novgorod, where the archaeologists found birchbark manuscripts between the layers of the preserved wooden pavement. This permitted the scientists to understand how the people from Novgorod were speaking in everyday life. However, the picture of the Old Ukrainian language could be deduced from the official written documents of the epoch, since the written language reflects the features of the spoken one. The two official letters (gramoty) of the Moldovia Principality (they date back to the second half of the 14th century AD) are considered to be the oldest documents which bear the principal peculiarities of the Ukrainian language. Further evidences are the letters addressed to the population of Halych (Galicia) by Kazimierz Wielki or Casimir III, the King of Poland: the part of them is written in Latin and there are those in the Ukrainian language in the form established by the Halytsian-Volynian (Galicia-Volhynia) principality. The common regularity with the above documents is foreign borrowings in the language of the Acts (the official documents). The point is that the Ukrainian language of Acts at the end of the 14th century was more close to the spoken style than that of the 15th and the 16th centuries. The latter was saturated with Belarusian-like and Polish-like words. The striking and detailed analysis on the historic, diplomatic and linguistic peculiarities of the Act documentation belonging to the Halytsian-Volynian principality at the 13th and the first half of the 14th century was written by historian Oleh Kupchynsky in 2004. This scientific work deserves the attention of the further publications.

The Ukrainian bookish language was developing in a way similar to the Ukrainian language of Acts. Its first evidences date back to the middle of the 15th century. However, the wider spread of the Ukrainian bookish language was observed at the second half of the 16th century. Deliberately, this language was oversaturated with the words and the grammar forms of the non-spoken sphere – those of the Old Church Slavonic language and of the Polish language. In some cases, the amount of the Polish words was so great in the documents that they seemed to be written in Polish but with application of the different phonetic and sign system.

Some researches have been claiming that this artificial character of the common language of Acts is chaotic and system-free. However, it was not a random mixture, in which every author could write as he desired, but quite a regulated language system.

“The simple language” was quite understandable, both Ukrainian and Belarusian, and the educated circles of the nation did not consider that it was necessary to follow the pattern of the Czech literature or the Polish literature, wherein the language of the educated class was built around the vernacular language as its coded supradialectal version.

The fact that the “high” language was the Old Church Slavonic language for all the Orthodox Slavic nations is explained by the pursuit of the educated ruling class to rely on the old traditions of the Motherland culture. Under conditions of the rise in ethnic self-consciousness, there arise the demand to search the “own antiquity”, roots. At the different stages of the development, all the East Slav documents were called “Russians”, but when required they were differentiated from the Old East Slavic Language (the language of the Kievan Rus) and the Old Church Slavonic language (“Slovenian” and “Slovenian-Russian”) and the Russian language; at the Ukrainian territories there appeared and spread the definition of “our simple language”.

Our land in the ancient times was a multicultural and multilingual array, included into the sphere of intercultural contacts. The usage of the Latin language at the territories of Ukraine and Belarus meant that these countries were the part of the Western Europe and the Central Europe, where Latin was the language of law acts, school, science and literature in the Middle Ages. Latin was used in the chancelries of the Halytsian-Volynian principality of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century, but from the middle of the 14th century, the foreign administration started to impose it. Later, however, the Latin language and teaching in Latin were associated rather with the western and catholic world. Some catholic authors called themselves Ruthenians, but this was not typical. Adoption of the Catholicism led to tearing the links with the Ukrainian tradition.

Being initially the language of the Polish population in Ukraine, the Polish language later spread to the whole region where resided the Polish, the Lithuanians, the Belarusians and the Ukrainians.

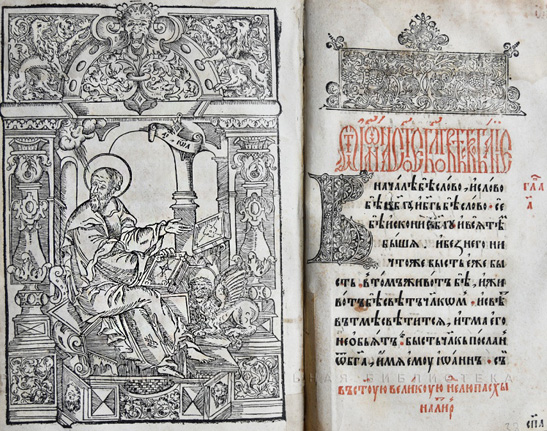

Implementation of printing was supreme in importance for standardisation in the majority of literary languages. The further stability in the Old Church Slavonic language was achieved in Ostrozka Bibliia (Ostroh Bible) publishing. Unlike Franciscus Scorina de Poloczko, who earlier aimed at bringing the language of the published Bible closer to the simple language of the Belarusians and the Ukrainians, the publishers of Ostroh (Ostrog), decided that the Biblical texts should be in the purer and sacred language. It was not surprising, since the fear to profane the sacred language was widely spread among the church figures of that time. Stanisław Hozjusz (Stanislaus Hosius), the ideologist of the Polish counter-reformation, expressed his fear that the new translations of the Bible into the Polish language could create the grounds for the free interpretation of the texts by readers: even women and tradesmen could “discharge the pastoral duty to teach”.

The revival of socio-political movement in the second half of the 16th century was accompanied by the stronger focus on the Old Church Slavonic language.

The cultivation of this language in Ostroh was linked with the activity of collegium (academy) located there.

Along with attaching great importance to the Old Church Slavonic language as the language of liturgy, theology, ruling class and culture, men of letters from Ostroh, however, started to use simultaneously the “simple” language as the tool for education, nonfiction writings, literary works. It was 1587 when the first works written in the simple language but not in the Old Church Slavonic language were published in Ukraine - A Key to Heavenly Kingdom, The New Roman Calendar by Herasym Smotrytskyi.

The norms of the Ukrainian bookish language were being elaborated by Demian Nalyvaiko, the famous poet and teacher at Ostroh academy. His translations into Ukrainian accompanied the original texts written in the Old Church Slavonic language.

The polemical writings were published into the Ukrainian, in particular Apokrisis by Khrystofor Filalet. However, for the polemical writings, the authors widely used the Old Church Slavonic language and the Polish language.

More conservative in this relation was the publishing house of Lviv Fraternity. Poems, school recitations and theatrical plays were published in a “simple” language. However, starting from the 1630s, this fraternity limited its publishing activities with conventional liturgical books and prayer books written in the Old Church Slavonic language. The valuable evidences of the Greek-Ukrainian cultural contacts are known as several publications with parallel texts in Greek and the Old Church Slavonic language. Along with Ostroh publishing house, the Lviv Fraternity continued printing primers in the Old Church Slavonic language in their publishing house, this activity was initiated by Ivan Fedorov. These primers and the dedicated grammar books promoted the establishment of norms not only in the Old Church Slavonic language but also in “simple” written language.

The Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra publishing house supported the Ostroh’s tendency of brining the variety into the publication assortment. The publishers here mainly employed the “simple language” for releasing written secular texts. Printing in the Ukrainian language required certain modifications in the Cyrillic script due to the specific features in the Ukrainian phonetics. For instance, along with the letter Г there appeared the letter Ґ (the latter was cancelled during the Soviet Period as the result of the approaching policy implemented to the related languages, but is renovated now in the contemporary Ukrainian grammar and spelling).

The Ukrainian language during the 13th and the first half of the 17th century was an important factor of the integrity of the Ukrainian lands, and the prerequisite of their cultural uniting. Along with the historic development of the Ukrainian nations, the Ukrainian language is acquiring its unique features.

Iryna Savchenko

Див. статтю "Дослідження розвитку української мови – ключ до її розуміння"

Our Advice for Reading:

Ісаєвич Я. Мовний код культури // Дніпропетровський історико-археографічний збірник. Вип. 1. На пошану професора Миколи Павловича Ковальського.– Дніпропетровськ: Промінь, 1997.– С. 290–307.

Ісаєвич Я. Українське книговидання: витоки; розвиток; проблеми.– Львів: Ін-т українознавства ім. І. Крип'якевича НАН України, 2002.– 517 с.

Огієнко І.І. Історія української літературної мови / авт. передм. М. Тимошик.– Київ: Центр учбової літератури, 2019.– 325 с.

Радевич-Винницький Я. Історія української мови: іноетнічні персоналії.– Львів: Апріорі, 2020.– 260 с.

Чумарна М. Королівство мови.– Львів: Апріорі, 2018.– 123 с.

Ющук І.П. Мова – найбільший скарб: статті.– Тернопіль: Навчальна книга; Богдан, 2020.– 358 с.